By Jan-Paul Heisig

As Europe transitions into so-called “longevity societies”—where people live longer and birth rates remain low—many regions are now experiencing steady population decline. This raises an urgent question for cities: how can they avoid losing population and remain attractive places to live?

Understanding what makes a city appealing has therefore become increasingly important for policymakers. Yet, surprisingly little is known about the specific features that draw people to one place over another. To help fill this gap, the Mapineq project (Mapping Inequalities Through the Life Course) designed and conducted an online conjoint experiment to explore people’s preferences and uncover the factors that make cities attractive today. The study was carried out in Finland, Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom.

Approximately 2,000 individuals per country were interviewed and presented with hypothetical cities that varied randomly across the following attributes: (1) Housing costs, (2) Unemployment rates, (3) Levels of theft and robbery, (4) Transport and cycling infrastructure, (5) Waiting times in public healthcare, (6) Number of higher education institutions, (7) Cultural venues and nightlife, (8) Parks and green spaces, (9) Air quality, (10) Trust in neighbours, (11) Openness to ethnic and sexual minorities, and (12) Number of immigrants from non-European countries.

Respondents were asked to compare seven pairs of cities with different combinations of these characteristics and to choose the city they would rather live in for each pair. This design allowed our Mapineq experts to estimate the relative importance of each attribute and identify the key factors that make cities attractive across the four countries.You can watch the presentations and discover key recommendations at our factsheet.

Affordable Housing: The Cornerstone of Urban Appeal

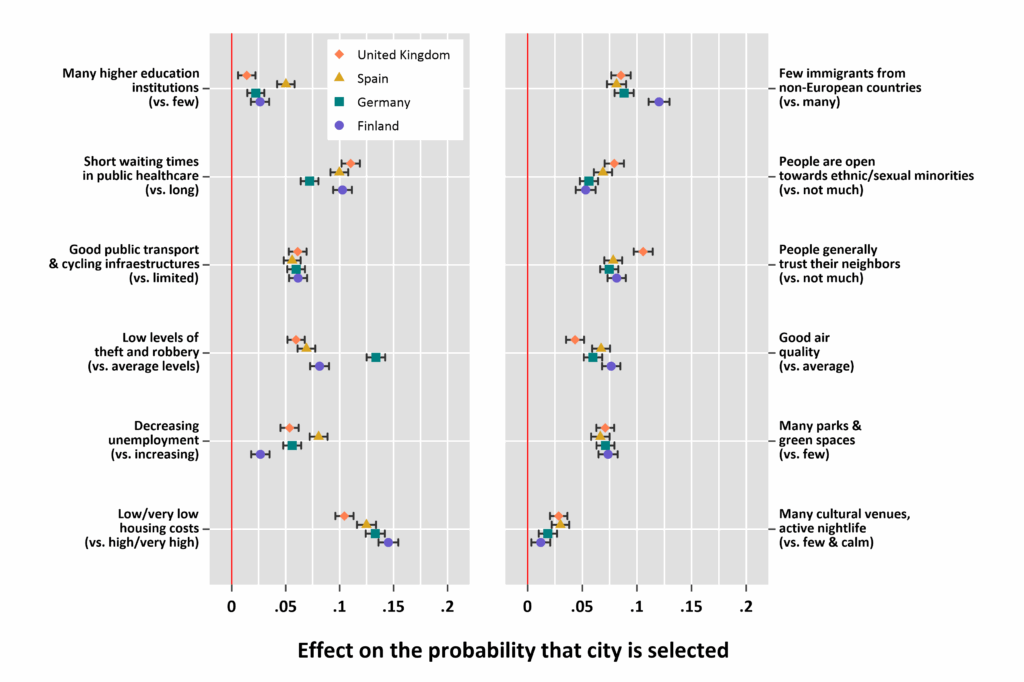

Housing affordability emerged as the single most influential factor in how attractive a city is perceived in three of the four countries. In the United Kingdom it was the second most important factor after short waiting times in healthcare (with the difference in effect sizes not being statistically significant). This finding highlights the central role of affordability in residential decision-making, regardless of national context.

Note: Confidence intervals are two-sided 83% confidence interval. Non-overlapping confidence intervals are approximately equivalent to the country difference in the effect being statistically significant at the five percent level (two-sided).

Country-Specific Patterns: Commonalities and Contrasts

Beyond housing, short waiting times to access public healthcare proved to be a particularly attractive feature in all countries—an indication of the value placed on timely public service delivery. Additionally, across all four countries, environmental quality was recognised as a relatively important driver of city attractiveness: Access to parks and green spaces was also rated highly, pointing to a shared desire for nature in everyday urban life. Respondents consistently favoured cities with good public transport and cycling infrastructure, underscoring the value of sustainable mobility.

Especially in the United Kingdom, respondents placed a strong value on openness and social cohesion: cities where people are generally open toward ethnic and sexual minorities were considered significantly more attractive. Trust in neighbours was also very relevant for them. Interestingly, some factors often associated with vibrant cities—such as cultural venues, nightlife, and the presence of universities—ranked lower in importance for most respondents.

In Finland, Germany, and Spain, respondents also rated cities with fewer non-European immigrants as being more attractive. However, this factor held slightly less weight in Germany and Spain than in Finland. This finding should be interpreted as a signal for action rather than a justification for exclusionary attitudes. The data highlights the persistence of underlying social biases that can shape perceptions of city life. Rather than accepting these preferences at face value, they underscore the urgent need for anti-discrimination policies and public education initiatives that promote intercultural understanding and inclusion. Fostering openness and acceptance—particularly through schools, media, and community programmes—can help build more cohesive and equitable urban societies, where diversity is seen not as a drawback, but as a strength.

Some differences by gender, level of education and income – but not too many

In Finland and the UK, women tended to place greater importance than men on access to healthcare and openness to population diversity when considering what makes a city attractive. In Finland and Germany, women also placed more value on access to green spaces. In Spain, no substantial gender differences were observed.

In all countries except Spain, highly educated respondents placed greater importance on openness to population diversity. Highly educated respondents also attached greater value to access to culture (Germany, United Kingdom), public transport infrastructures (Finland, Spain), and clean air (Finland, Spain) compared to their less educated counterparts. At the same time, they were more accepting of non-EU citizens (Finland, UK) and slightly less concerned about housing costs (Germany, UK). The latter, unsurprisingly, also applied to those with high rather than low incomes, a consistent pattern found in all four countries.

Finally, compared to older respondents (aged 40 and above), younger individuals (aged 39 and under) tended to place less importance on a range of factors when evaluating what makes a city attractive. For example, in Germany, younger respondents were less concerned about unemployment, trust in others, transport, green spaces, crime rates, and immigration.

Somewhat unexpectedly, younger respondents in Germany were also less sensitive to housing costs. In the UK, younger individuals gave less weight to social trust, immigration, and access to green spaces. In Spain, younger respondents placed less emphasis on immigration and healthcare. In Finland, openness to diversity was more important to younger individuals than to older ones, while social trust and access to healthcare mattered less to them.

Overall, differences across groups, even when statistically significant, were mostly modest in size. While sometimes meaningful and often consistent across countries, the overall picture emerging from these comparisons across major social groups is one of subtle differences rather than stark divides in what people value in cities.

Discussing Results in National Contexts

The results of the conjoint study have been presented and discussed within specific national contexts through events involving experts from academia, policymaking, and civil society organisations. Discussions were organised around key thematic areas, including: families, higher education, housing, and biases in individual perceptions.

These country-level events provided valuable opportunities to contextualise the findings, explore policy implications, and engage stakeholders in meaningful dialogue. You can access detailed reviews and summaries of each national event on the Mapineq website.

This article is based on this post, by Jan-Paul Heisig first published on Population Europe.